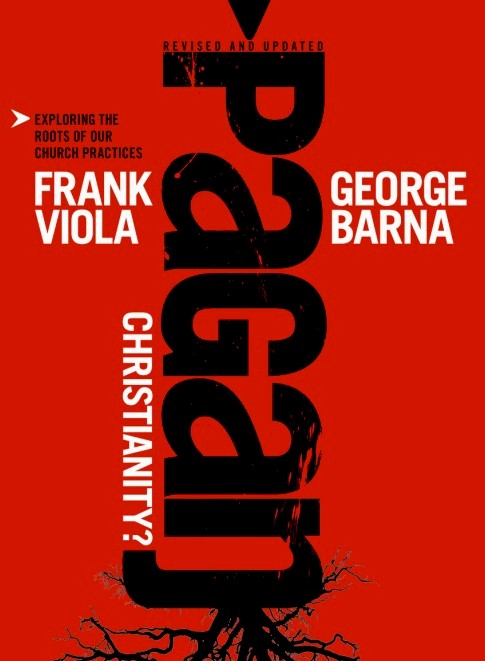

The basic thesis of this book is that traditional Christianity has adopted a number of practices that are not in the New Testament, and that these practices should be eliminated. When the authors refer to "traditional" Christianity, they mean both Protestant and Catholic churches - the critiques in this book are mainly directed to American evangelical churches. Sometimes Viola and Barna talk about the "institutional church", which they contrast to "organic" churches, or "house" churches, which are evidently preferable.

The basic thesis of this book is that traditional Christianity has adopted a number of practices that are not in the New Testament, and that these practices should be eliminated. When the authors refer to "traditional" Christianity, they mean both Protestant and Catholic churches - the critiques in this book are mainly directed to American evangelical churches. Sometimes Viola and Barna talk about the "institutional church", which they contrast to "organic" churches, or "house" churches, which are evidently preferable.So what are these pagan practices? The authors focus on church buildings, paid clergy and sermons.

Perhaps the third one causes the most surprise - isn't there a lot of preaching in the Bible? There certainly is - but Viola and Barna argue that Old Testament prophets "spoke extemporaneously and out of a present burden, rather than from a set script" (p. 87), while what the New Testament apostles did is not normative for the Christian church. They planted churches and then moved on - and so the sermon is only appropriate for a church in its infancy. The biblical model for the church, our authors aver, is the full congregational participation as described in 1 Corinthians. In the same way, Viola and Barna argue that pastors simply get in the way of this every-member-ministry.

The book has a lot to say about how, particularly under Constantine, the church picked up ideas from the Graeco-Roman world. They also argue that the church carried over unhelpful things from its Jewish background. Thus, the church building is modelled on both the pagan shrine and the Jewish temple. The payment of clergy comes from both the paid Greek rhetoricians and the Levitical tithe. Clerical garments come from both Roman officials and Old Testament priestly garb. All these things, Viola and Barna argue, are not in the New Testament, and therefore do not belong in the church today.

There are two points, then - firstly, that these things are not in the New Testament, and secondly that it is wrong to practice them.

It is easy to think of New Testament verses about preaching. There is 2 Timothy 4:2 - "Preach the word; be ready in season and out of season..." But Viola and Barna say that this doesn't apply, because "Timothy was an apostolic worker" (p. 102). There is 1 Corinthians 9:14 - "In the same way, the Lord commanded that those who proclaim the gospel should get their living by the gospel." The authors don't deal with this verse - instead there is an annoying footnote on p. 178 that a "response to those biblical passages that some have used to defend clergy (pastor) salaries" can be found in Viola's book Reimagining Church.

Actually, the authors reject the whole idea of "verses", and devote a whole chapter to critiquing the idea of prooftexts. They reject the idea that Acts 14:23 means that every church should have elders, since it "is referring to an event in south Galatia during the first century" (p. 235). They reject the idea that 1 Corinthians 16:2 supports a weekly offering since it's "dealing with a onetime request" (p. 236). Strangely, however, they do view 1 Corinthians 14:26 ("every one of you has a psalm") as normative (p. 166).

The second point, then, is that it is wrong to do these things if they are not supported by the New Testament. Most Christians would agree that church buildings are not in the New Testament, but would think there is nothing wrong with them. Viola and Barna, however, argue that they "limit the involvement of and fellowship between members" (p. 44).

This is a radically biblical approach to ecclesiology. It was strange, then, reading this as a Presbyterian. For the Westminster Confession of Faith affirms that God is not to be worshipped in any way "not prescribed in the Holy Scripture" (XXI.1). In this way, Viola and Barna are simply following the Regulative Principle of Worship, albeit with different emphases. For example, many proponents of the Regulative Principle use it to forbid musical instruments in worship. Viola and Barna note that "there is no evidence of musical instruments in the Christian church service until the Middle Ages" (p. 162) but they don't seem to view it as one of those evil, pagan practices. Now, the Confession distinguishes "elements" of worship, which always must be found in Scripture, and "circumstances" which "are to be ordered by the light of nature, and Christian prudence" (I.6). I have always thought instrumentation was one of those elements, as, indeed, church buildings would be. So I think we need to reject the argument that unbiblical practices are necessarily wrong.

Viola and Barna insist that we need to worship as they did in the first century, while at the same time reject the idea that the Book of Acts is a model for us. This strikes me as rather inconsistent. They emphasise the distinction between prescriptive and descriptive passages, but seem to privilege 1 Corinthians over Acts, seemingly without considering that the worship in 1 Corinthians (which has everyone sharing words of exhortation) may be merely descriptive as well. The great emphasis on preaching in Acts is simply discarded.

Finally, the rejection of pastors goes hand in hand with an anti-hierarchical approach. Viola and Barna appeal to Kevin Giles to back up their ideas. Giles has argued that the Son is not eternally subordinate to the Father. Yet the authors appeal to him and assert that historic orthodoxy rejects the eternal subordination of the Son (p. 264), without apparently realising the controversial nature of Giles' position, or the arguments against it.